Tuesday, 20 November 2012

Symbiotic Postures Of Commercial Advertising And Street Art. And Street Art Rhetoric for Creativity Stefania Borghini, Luca Massimiliano Visconti, Laurel Anderson, and John F. Sherry, Jr. ABSTRACT: An ongoing tension between new ways of achieving novel, meaningful, and connected forms of expression is permeating the practice of advertising and igniting a lively academic debate. Novelty and social connection have long been preoccupations of art worlds. In this paper, we explore the creative tensions and synergies between countercultural and commercial communication forms of street art and advertising. Viewing each form as a species of rhetoric, we analyze a set of rhetorical practices employed by street artists that not only reflect, but might also be used to shape, commercial advertising in the near future. - Taken from 'Quest"

Advertising has been acknowledged as art (Twitchell 1996)

and christened capitalist realism (Schudson 1984). Even though

rhetoric in advertising has different purposes compared to

art (e.g., El-Murad and West 2004), the rhetorical process

in the two contexts is similar (White 1972; Zinkhan 1993).

In the same way art influences and gives meaning to our life,

advertising shapes contemporary consumer culture (e.g.,

Elliott 1997; Willis 1990). As art mirrors the shared truths,

ideals, and metaphors of a given society, advertising reflects

our popular culture. As art embodies universal fantasies,

feelings, and thoughts, advertising expresses the rational and

emotional experiences and moods of consumers. Rhetoric in

both art and advertising is strictly influenced by the social

context within which it originated (e.g., Csikszentmihalyi

1999).

A parallel art form that poses a creative challenge for the

advertising industry is the one we categorize as the global

Street Art Movement, or, more simply, street art. Street art

might be characterized as capitalist surrealism, postmodern

realism, or perhaps even as “subvertising” as it converts,

diverts, and inverts advertising proper to promote noncommercial consumption. In this paper, we analyze street art as

a species of advertising, explore the use of advertising by

street artists, and examine the implications of street art for

advertising creativity. We focus in particular on the potential contributions of the creative rhetoric employed by the

stakeholders of street art to advertising practice.

As with its commercial counterpart, street art is a product

that embodies its own advertising. Seen as a countercultural

response to commercially or statist-induced alienation, street

art is a populist aesthetic, a consumerist critique, and an

urban redevelopment project. Street art espouses a vision of

space reappropriated as place, where commercially noisy or

entirely silent streets are reclaimed by artists for their proper

“owners.” Iron shop gates become canvasses for publicly held

open-air museums. Subway trains become moving installations conveying subversive meaning to residential areas.

Such subvertising parodies, appropriates, and occasionally

capitulates to its commercial counterpart.

Street art has the visual and cognitive effect of commercial

advertising, and many of its brand dynamics, but carries messages of enjoyment, ideological critique, and activist exhortation rather than of commercial consumption. It offers both an

implicit and explicit challenge to advertisers, who ultimately

will be tasked with appropriating street art’s authentic essence

to revitalize their own commercial efficacy (Holt 2002).

Street art can be framed as advertising, promoting the

artists as well as their ideologies. Moreover, it can be framed

as an alternative template for advertising. Some street artists

are employed in the advertising industry, and some aspire to

become advertisers. Some street art is used for commercial

advertising purposes, in both legitimate and faux forms. Some

street artists rail against advertising and the consumer culture. However advertising is imbricated, street art has a multistranded relationship with its commercial counterpart.

Relying on a long-term ethnographic and netnographic

(Kozinets 2002) engagement with the global Street Art Movement, in this paper, we analyze a set of rhetorical practices

employed by street artists that not only reflects, but might also

be used to shape, commercial advertising in the near future. We

approach the craft of advertising as rhetoric (Deighton 1985;

McQuarrie and Mick 1992; Pracejus, Olsen, and O’Guinn

2006; Scott 1994b; Scott and Vargas 2007) where symbols are

used to persuade and take into account the visual aspects of

advertising (Kenney and Scott 2003; McQuarrie and Phillips

2005; Scott 1994b; Scott and Vargas 2007). We contribute to

the existing knowledge on the rhetorical process of advertising

and identify strategies that can be applied in order to enhance

creativity (El-Murad and West 2004). The rhetoric in street

art can stimulate advertising practice in two domains: idea

generation (e.g., Reid and Moriarty 1983) and social engagement (Ang, Lee, and Leong 2007).

the rhetoric oF AdVertiSing

And Street Art

rhetoric and creativity

Rhetoric is a pervasive trait of both commercial and noncommercial creativity in communication. We use the term rhetoric

to address both verbal and visual street interventions. Initially,

rhetoric was considered an exclusive domain of verbal language

(Kenney and Scott 2003). Recently, the issue of visual rhetorical practices has entered the advertising researchers’ agenda

(Bulmer and Buchanan-Oliver 2006, p. 55; Pracejus, Olsen,

and O’Guinn 2006; Scott 1994a, 1994b). Hence, an analysis

of visual rhetoric considers how images work alone and collaborate with other elements to create an argument designed

for moving a specific audience. In this light, advertising and

street art share a common interest in elaborating communication structures that inform and persuade their audiences.

Recently, there has been a demand for the development

of a general theory of advertising creativity (e.g., Reid and

Rotfeld 1976; Smith and Yang 2004; Zinkhan 1993) for

which a rhetorical approach holds much promise. Scholars

have applied contributions from psychology and adapted their

prescriptions to advertising. Blasko and Mokwa (1986, 1988)

adopt a Janusian approach, which is rooted in the logic of paradoxical thinking, apparently opposite or contradictory ideas

that can be resolved and accepted by an appropriate emotional

mental processing. Reid and Rotfeld (1976) have proposed an

associative model of creativity that shows a relevant relationship among some specific copywriting abilities and attitudes.

Novelty actually involves uncertainty of outcomes (Sternberg

and Lubart 1999) and, as a consequence, creativity involves risk

(West 1999; West and Berthon 1997; West and Ford 2001).

Empirical evidence shows that an attitude toward risk taking

is linked to higher levels of creativity as measured in terms of

advertising awards won (El-Murad and West 2003).

Interestingly, each of these elements (paradoxical thinking,

associative ability, and novelty/risk taking) is also reflected in

street art visual rhetoric. We thus demonstrate that advertising creativity can be studied as rhetoric (Deighton 1985;

McQuarrie and Mick 1992; Pracejus, Olsen, and O’Guinn

2006; Scott 1994b; Scott and Vargas 2007). Advertising is

rhetorical communication, and creativity has to serve this goal.

Our study focuses on emergent visual rhetorical practices that

can inspire advertisers.

Social use of Advertising

When investigating the intersections between street art and

advertising, the social use of advertising by its audiences needs

consideration. The current debate on existential consumption

(e.g., Elliott 1997; Firat and Venkatesh 1995; Willis 1990)

considers consumer creativity as a form of agency that is carried out within the constraints imposed by the hegemony

of the market (e.g., Goldman 1992), often expressed as the

manipulation and reinterpretation of advertising by active

consumers.

Advertising is a cultural product consumed symbolically

by consumers independently of the products being promoted

(Elliott 1997; Willis 1990). While some authors have advocated a deeper understanding of this phenomenon (e.g., Ritson

and Elliott 1999; Scott 1994b), the social use of advertising has

been an underdeveloped research topic. Some exceptions have

shown that advertising messages have a cultural meaning in

everyday life (McCracken 1988), are an incentive for word-ofmouth conversations (Sherry 1987), represent a way to reveal

an individual viewpoint to others (Mick and Buhl 1992), and

influence existing rituals (Otnes and Scott 1996). Consumers

are aware of the rhetorical conventions of advertising and are

able to interpret its rules of language in the same way they

are able to understand visual conventions applied in movies

(Pracejus, Olsen, and O’Guinn 2006).

Young people are particularly prone to engaging in the

creative use of material culture in their daily lives (O’Donohoe

1994, 1997; Ritson and Elliott 1999; Willis 1990). They

elaborate meanings, combining the irony, playfulness, and

ephemerality of advertising. They manage a vast repertoire

of codes and conventions typical of advertising messages,

revealing a combination of control and power over advertising with a certain degree of vulnerability (O’Donohoe 1997).

Moreover, through the processes of consumption, young consumers produce “grounded aesthetics” (Willis 1990, p. 21)

that make the consumption of advertising vital and pleasant,

emphasizing the search for beauty through the symbolic use

of common culture, experienced and reinterpreted as an authentic form of art.

Streets and walls provide the virtual and physical grounds

where social interpretations and manipulation of ads are performed. According to our field notes, conversations are not the

only privileged way to share interpretations and build social

meanings around advertising. Texts produced by consumers

are alternative forms of grounded aesthetics, a different form of

intertextuality where the creators are able to interlace market

ideologies and codes with resistance and rebellion. The creativity of these forms of material culture easily becomes popular

and appreciated by dwellers in public spaces.

MethodoLogy

Our study is a multisite ethnography and netnography

(Kozinets 2002; Sherry and Kozinets 2001) of street art. This

methodology is consistent with our objectives since we are focusing on the symbols and meanings of rhetoric (Scott 1994b)

and on cultural practices of creativity by street artists and

advertisers (Arnould and Thompson 2005). As a transcultural

phenomenon, street art exhibits both global commonalities

and local nuances. From 2005 through 2008, we conducted

naturalistic inquiry with global Street Art Movement stakeholders (e.g., street artists, passersby, public institutions, etc.)

in several cities in Europe (Milan, Pavia, Turin, Rome, London,

Dublin, Brussels, and Amsterdam) and the United States (San

Francisco, Phoenix, and Minneapolis). Netnographic inquiry

expanded our observations to many other sites. We immersed

ourselves in the phenomenon, attending events and monitoring news and reportage presented in the local press and mass

media.

Our multicultural, bigender research team included four

principal investigators and several assistants. Its composition

allowed us to function as both insiders and outsiders in the

inquired cultural contexts, which facilitated access during

data collection and sharpened interpretive acuity during data

analysis (Sherry 2006). Researchers operated as individuals,

dyads, and triads, and held periodic strategy and analysis

meetings as both full and partial groups. Internet connections

permitted teammates to share new data, emerging insights,

and local media coverage of street art in real time.

Because street art is illegal in the cities we studied, trust

building was a crucial component of our research. Participation

was elicited through our habitual presence, personal contacts,

key informants, snowball sampling, and word of mouth. By

establishing trust with one street artist, we often gained

acceptance with a network of street artists throughout the

country. Most interviews ranged between two and eight hours,

and informants were usually both observed and interviewed

iteratively. We conducted personal in-depth interviews with

12 key informant artists in Italy and 8 in the United States.

The ongoing exchange with these informants allowed us to

investigate the activity of the most important groups and artists in our field sites. We also interviewed 60 consumers in the

act of appreciating art or retrospectively commenting on their

experience. Netnography was appropriate given the extensive

diffusion of street art images throughout the world on street art

sites and blogs. We monitored these sites and blogs, obtaining

information on activities, thoughts, and critiques of both street

artists and consumers. Examples of these sites included www.

woostercollective.com, www.banksy.co.uk, www.graffitti.com,

www.streetsy.com, and www.thedisposablehero.com.

Data were recorded electronically and manually. Field notes

and verbatims of interviews were transcribed and photos and

videos were classified according to multiple criteria. We built

a data set of 800 pages of transcriptions, 58 pages of blogs on

the Internet, 450 photos, and 15 hours of video. Data were

analyzed and interpreted according to conventional qualitative

research standards (Arnould and Wallendorf 1994; Hirschman

1986; Kozinets 2002; Lincoln and Guba 1985; Spiggle 1994),

and involved member checking, horizontal and vertical analysis, and an ongoing comparison of details by tacking back and

forth between the particular and the general. Specifically, emergent themes and patterns were identified. These interpretations

developed over multiple readings and the interaction between

previous and emerging insights (Spiggle 1994).

While verbal data and narratives inform and sustain our

interpretation, in this paper, we rely more on visual data in

our representation to mirror the prominence given in the literature to the visual aspect of advertising (Kenney and Scott

2003; McQuarrie and Phillips 2005; Scott 1994b; Scott and

Vargas 2007). Thus, we employ the same hermeneutic strategies of close reading and deconstruction that researchers in

the consumer culture theory tradition have imported from art

and literary criticism and applied to advertising in particular

(Scott 1994a; Stern 1996) and material culture in general (Belk

and Sherry 2007) to reveal the rhetorical practices at work in

our electronic corpus of images. We provide examples of each

practice as sedimented in street art itself.

FindingS And diScuSSion

contemporary Street Art and commercial Advertising

Street art is a global phenomenon that encompasses several

physical and virtual forms of expression, including traditional

and stencil graffiti, sticker art, video projection, urban design,

tags, art intervention, poetry, and street installations. The formerly monolithic aura of the global Street Art Movement as

an illicit practice is losing its ideological primacy, giving way

to perspectives that encourage a coexistence with institutional

forces such as government and the market.

The current era of street art has become associated with

cultural trends such as fashion, music, popular art, sports, movies, video games, entertainment, and advertising. Companies such as Sony, Ikea, Saatchi, Nokia, Porsche, Opel, and Diesel

have borrowed the aesthetic of street art in order to give their

products an urban and artistic aura. Street art is thus institutionally celebrated and acquires an increasingly legitimate

cultural role.

This cultural conjoining of art, marketing, and urban discourses has progressed to the point that the typical dwellers of

public spaces find it harder to distinguish between authentic

and spontaneous street art and commercial messages. Boundaries blur into an emerging picture that fosters new creative

expressions culminating in the following main street art rhetorical practices identified as themes during our analysis.

Visual rhetoric of Street Art creativity

Despite growing interest in street art evinced by popular media

as well as by managers and academics, no previous research

has adequately investigated the nature of street art creativity

or questioned its potential effect on advertising practices.

In this paper, we explore the implications of the rhetorical

practices generated by street artists that we discerned in our

study for creating more effective, contemporary, and socially

sensitive advertising. The patterns of practices and the communication codes elaborated by street artists can be borrowed

by agencies to nurture creative processes and stimulate future

campaigns. In particular, we illustrate seven rhetorical practices found in our research: (1)aestheticization, (2) playfulness

and cheerfulness, (3) meaning manipulation, (4) replication,

(5) stylistic experimentation, (6) rediscovery, and (7)competitive collusion.

Table 1 anticipates the following discussion of rhetorical

practices, of their intertextuality with contemporary advertising, and of the possible contribution in terms of advertising

creativity. Parallels as well as distinctions emerge from opposing street art and advertising, which reciprocally benchmark,

replicate, and subvert established rules. Each rhetorical practice

can be explored and rigorously deployed in advertising and

in street art like other techniques, and steps are suggested for

creative processes (e.g., Bengtson 1982; Blasko and Mokwa

1986, 1988; Johar, Holbrook, and Stern 2001).

Aestheticization of Functional Media

Street art is rooted in rebellion against institutional reality

and its multiple forms of oppression. Contemporary street art

reverses this original logic while sharing the idea of stimulating consumer identity and agency. We found the graffiti of

urban defacement to be overcome by forms of intervention

marked by a quest for pleasant aesthetic effect. Current graffiti,

tags, stencils, stickers, murals, and other forms of street art

are designed to achieve higher levels of aesthetic performance

and response.

Our study indicated that urban design is perhaps the most

remarkable example of aestheticization. Some artists produce

creative works that give an aesthetic value to functional, everyday objects in public spaces. Garbage cans, curbstones, and

asphalt are painted and transformed into playful objects, full

of humor and cheerfulness (Figure 1).

The celebration of hedonic traits of production and consumption and the quest for aesthetic quality spur street artists

on to ever higher performance. Here we observe a parallel with

commercial advertising practice, as far as beauty and pleasant

aesthetic impact of communication is concerned. Nonetheless, street art emphasizes the opportunity arising from the

aestheticization of frequently forgotten functional media and

displays (e.g., walls, curbstones, garbage cans, stairs). Mirroring or replicating this rhetorical practice, advertising creativity

can be fostered through an innovative use of traditional media

(e.g., placards, posters, boards), or through an ongoing tryout

of new and unconventional media (e.g., sculptures, parking

lot floors). Recent studies (Dahlen 2006; Sasser, Koslow, and

Riordan 2007) have shown that creative media choices can

facilitate consumers’ perceptions of ads and thus enhance brand

attitudes. Street art practice might encourage managers to

imbue traditional commercial ads with new functions such as

decoration, curiosity, surprise, or entertainment, or to utilize

new unconventional media as suggested above.

Playfulness and Cheerfulness

Most newer street art relies on a language dominated by playful and cheerful codes in contrast to the at times melancholy

of contemporary towns. Characters, subjects, forms, shapes,

styles, and colors are often borrowed from cartoons and comics,

giving rise to the “cartoonification” of urban landscapes. Our

passersby consumers suggested that walking in the decorated

streets was similar to reading a fairy tale liberating them from

the mundane experience of living in ordinary towns.

The border between the serious and the humorous is often

transgressed, and the result is a creative mix of meanings.

Novelty, an intrinsic feature of creative products, converted

dull aspects of everyday life into meaningful or light-hearted

ones. As one of our artist informants observed:

If the world is gray, we do try to color it a little bit. . . . It is

a fantastic world through which we all try to create a world

better than our reality. . . . Personally, I feel like a clown, a

juggler who works in the streets . . . to offer a smile. I want

to enforce the idea of public space as a meeting place, which

helps people feeling better. (Pao, Milan)

The mode for this rhetoric is an apparently childlike representation of reality, which may translate any stimulus from

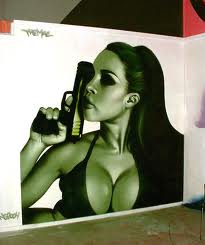

everyday life into humorous symbols. Even when the perspective is critical and the aim is to subvert the existing market hegemony, the codes can nonetheless be amusing (Figure 2).

The lesson for advertising is that playfulness as a rhetorical

practice can impart a fresh, positive look, which helps engage

the audience’s attention and melt its perceptual and cognitive

resistance.

As far as advertising creativity is concerned, this implies

reaching and maintaining a certain connectedness with the

audience (Ang, Lee, and Leong 2007) based on the offering

of pleasant representations of reality symbolically given as a

gift. Even though this may imply a higher degree of risk with

some clients (West 1999; West and Berthon 1997; West and

Ford 2001), it may force advertisers to explore as a habitual

creative practice the opportunity to transform ordinary and

dull entities into playful and cheerful ones. This mental exercise can diversify creative processes (Johar, Holbrook, and

Stern 2001).

Manipulation of Meanings

The third rhetorical pattern that we observed was détournement. Détournement is the practice of playfully recombining

the elements of a particular discourse in such a way as to subvert the meaning of that discourse. Street art is a multicultural

mélange, part melting pot and part mosaic. In borrowing

contents from other cultural domains (politics, marketing and

advertising, popular arts), street art appears “multivocal” and

“eclectic” (Brown 1993; Firat and Venkatesh 1995). As such,

street art also mirrors the symbolic and syncretic nature of commercial advertising (Twitchell 1996) and adopts an attitude

toward divergence that suggests ways to foster advertising

creativity (Smith and Yang 2004). We found the material and

stimuli provided by these institutions were employed in unexpected ways, in keeping with the détournement methodology in visual rhetoric proposed by Debord and Wolman (1956;

see also Harold 2007; Moore 2007). In our case, this involves

destabilizing the dominance of advertising by incorporating

elements of advertising into a new aesthetic creation.

The power of détournement originates from the double

meaning and the enrichment created by the coexistence of

old and new senses. Street artists built bridges across and

linked distant concepts. The beard can be the visible traitd’union for political leaders belonging to different moments

in time and space (Figure 3). The historical and political

cross-references were sarcastically contrasted, and the images

of these leaders were contextually elaborated in stylized and

artful ways.

In addition, icons were deployed in oppositional terms,

contrasted to their original purposes (Figure 4a). This was

often accomplished by a transfer of symbols to spaces that

were ideologically in opposition to the key message of the

artwork (Figure 4b). Using this rhetorical practice, street

artists were fond of elaborating on companies’ brand logos

and advertising images. In 2005, Banksy (www.banksy.co.uk),

for example, coined the term “brandalism” (Moore 2007) to

define those practices of street art aiming to short-circuit the one-way communication of established brands and declaim

the independence of the individual voice.

The rhetoric of manipulating divergent cultural meanings

holds three implications for advertising that would enhance

effective and creative communication targeted to urban

dwellers: (1) the contamination of codes, which are melted

or juxtaposed and transformed into completely new contents;

(2) the decontextualization of symbols, icons, and brand

logos, which find fresh associations given the new terrain of

their location; and (3) the interplay between images and their

places, which emphasizes the need for contextualized creative

communications. In so doing, communication signifiers are

first decontextualized to grant innovative meaning and later

recontextualized in consistent urban settings.

Replication of Symbols and Messages

Replication was the essence of the broadcast strategy of street

artists. In this rhetorical practice, advertising was a reference point for street artists who benchmark, replicate, and

subvert established managerial rules. Not surprisingly, most

street artists exuded a certain degree of confidence in their

grasp of managerial praxis, as they were critical consumers

themselves.

Mirroring and integrating advertising practices, the rhetoric of mass replication observed the following steps: (1) the

construction of a unique and recognizable personal/collective

creative template, (2) the transfer of some shared street art

values to this template and its replication through connected

variations, and (3) the adoption of a variety of media to masscommunicate and replicate the message.

Building distinctive and pleasant creative templates

(Goldenberg and Mazursky 2002) fueled success both within

the street artist community and across its target audiences.

Distinctiveness was variously achieved by adopting (1) specific

subjects (e.g., Pao’s penguins, Ivan’s poetry), (2)recurrent traits

(e.g., Bros’s stylized vertical eyes that animate every conceivable urban object), (3) personal logos (i.e., the previously

mentioned “tags” and other individual or collective brands),

and (4) unique space/supports (e.g., again, Pao’s predilection

for curbstones; Figure 1).

Through meaning transfer and replication, street artists

crystallized their specific creative style. Thanks to replication,

each individual or collective group benefitted beyond his/

her/its personal value. It was common to observe commercial

merchandising that resembled artists’ languages or to witness

market trading for street artists’ works. Replication typically

occurred through different levels of variation (Figure 5), which

stimulated both attention and recall as happens with creative

advertising (Stone, Besser, and Lewis 2000; Till and Baack

2005).

Finally, creative templates and messages were masscommunicated. Street artists spread their logo using various

media, from the traditional (i.e., walls and public spaces) to the

unconventional (personal Web sites working as virtual walls,

merchandising, museums, and markets). This broadcasting

system was described by our informants as a way to give creative outputs greater visibility. Several audiences thus become

acquainted with the multiple expressions of street art and may

even have used these symbols to inform their clothing style,

or to build social discourses (Willis 1990).

This rhetorical practice is already most resonant with

commercial advertisers, so a simple statement of lessons to be

reinforced from the street should suffice. Evocative symbolism

is essential not merely for establishing memorability but also

for creating community. Replication through unusual placement of messages encourages consumers to receive content not merely as an epiphany but also as a gift from the source.

The unexpected delight produced by these little discoveries

is a powerful bonding agent.

Stylistic Experimentation

Cautious in labeling themselves as artists, writers openly

stated that they do not perceive their work as “art” in the sense

that they were not entering any philosophical debate about

aesthetics. Their concern was directed toward the social and

stylistic dimensions of their work. As such, street artists did

not subscribe to dominant aesthetic rules, but acted to gain

attention from dwellers. By renouncing artistic sacralization,

the rhetoric of stylistic experimentation allowed freedom in

the search for more powerful communicational codes (e.g.,

through provocative interplay between the work and its place;

Figure 4b) that ensured exposure, attention, interpretation,

and retention (Aaker, Batra, and Myers 1992). Stylistic experimentation involves audiences by means of (1) replicability, which increases the chances of exposure and retention;

(2) desirability, which breaches the barriers of audiences’

attention; (3)accessibility, which strives for easily understood

codes interpretation; and (4) participation, which is the artists’ ability to involve passersby in discursive activities and

behavioral changes.

Replicability was attained through multiple techniques

and media: writing, stickers, stencil, and urban design. While

some of our informants specialized (e.g., Ivan’s poetry, Pao’s

urban design, Obey’s stickers), others hybridized and diversified their stylistic codes (e.g., Bros operates through graffiti,

stencils, stickers, and even canvasses).

Desirability and accessibility were accomplished through

the emulation of famous artists’ styles, and icons were used

in a strategy of manipulating familiar and accessible communication codes. Examples were countless: Warhol and

pop art represented a dominant genre, but surrealism (e.g.,

Dalì, Max Ernst, Magritte), informalism, and action painting (e.g., Pollok, Rothko, Vedova) were also appropriated

(Figure 6).

Finally, the stylistic experimentation of street artists elicits

audience’s participation in ways that may inspire advertisers in

the search of socially inspired and effective communications.

These ways include (1) intimacy, which artist communicators gained through dialogues and by dwelling in the audience’s space; (2) amusement, which softens criticism of the

dominant culture; (3) familiarity, derived from the adoption

of well-known cultural codes later translated into new fields of

meaning; and (4) bidirectionality of communication, fostered

by incomplete or challenging messages. Transfiguration as Restitution

Street art rediscovers the unseen. Street art stakeholders participated in the visionary quality of creativity, as they continuously

rediscovered forgotten spaces and dimensions of urban life. As

one walks the streets, attention is typically captured by the city

skyline, the shops, or other passersby. As a consequence, many

other places are invisible. Through playful codes and virtuous

spectacular performance, street artists celebrated unusual and

lost areas of towns. Stickers was occasionally placed at the

tallest heights of buildings or streetlamps, which required

heroic effort by the artist. Alternatively, stickers were placed

at ground level so as to evoke the infinitesimal scope of mundane life. Macrocosmos and microcosmos were encompassed

in these stickers (Figure 7). In other cases, artworks covered

neglected and vulgar pieces of urban landscapes: floors, stairs

and handrails, benches, garbage bins, curbstones, junction

boxes, or shops’ iron gates. Through street art, pedestrian

material was brought to (new) life: pieces of poetry fill the

lines of subway stair-steps, colorful frogs jump onto road signs,

and garbage bins or junction boxes become trendy displays of

urban design (Figure 8).

Rediscovery is built on the attribution of voice to previously silent meaning carriers. Instead of adding “conversation”

to crowded areas, street artists redirected such conversation

toward new horizons. Mainstream communications were

surpassed through the exploitation of previously silent corridors. Transfiguration goes beyond the mere aestheticization

of cities, since it aimed to reanimate the invisible landscape of

everyday life. Interestingly, where advertisers aim to reduce the

consumer’s sight-scope to one single purchase option, street

artists strive to extend the capability of passersby to observe

normally unobserved, invisible urban lands.

This rhetorical practice offers insights for advertising since

transfiguration highlights the relevance of the following tenets:

(1)transformation as regeneration, which celebrates a paradoxical form of communicating (i.e., things are changed in order

to become visible as they are and appreciated for their original

meanings); (2) oversizing and downsizing, which increase

the chance of gaining unexplored venues for communication

through the discovery of “out-of-touch” territories of meanings; and (3) ennobling as the capability of making silent or

marginal topics more vocal and central ones. Transfiguration as

restitution is the opposite of détournement since transformation is not directed toward subverting meanings but toward

making visible the “true” meaning of unquestioned space.

Competitive Collusion

Street art often exhibited a confrontational character. The creative factory founded by Andy Warhol in New York in 1963

represents a useful metaphor to describe the way street art replicated, perhaps subconsciously, the logic of these creative

labs, where individual work is intertwined with others’ codes,

behaviors, and narratives.

Street art’s factories are living examples of “creative socialism,” evoking communal values, democracy, denial of

hierarchies, and open sourcing of both creative outputs and

cultural competencies.

This confrontation assumed multiple forms. It involved

criticism, competition, evaluation, negation, and legal reactions as well as pride, cooperation, collusion, and creative

partnership (Figure 9a). The only recurrent trait in this

confrontational ethos was the celebration of respect beyond

occasional conflicts and groups’ parochialism nurtured by

street artists’ strong tie to the territory. An unwritten and

now largely respected rule states that no street artist has the

right to destroy the work of another (Figure 9b). It was common to observe walls with sets of interventions, each of them

visible and attributable. They comprised a kind of open-air,

open-source collection with a free ticket for all:

A writer seldom writes alone. He creates a group. . . . People

you meet and who love the things you do. . . . I give friendship

great importance. To me, the memories of these guys, even

now that I don’t see them anymore. . . . We shared moments

of fear, of pride, of happiness. . . . We were partners! (Poo,

Milan writer)

Respectful confrontation illuminates the praxis of street

art communication by highlighting: (1) the rejuvenation of

creative collective movements (i.e., the progressive dismissal

of solipsism and self-referentiality); (2) the formula of competitive collusion, as a vital combination of reciprocity and

sound individualism; and (3) the territorial rooting of contemporary communication flows (“tell local, speak global”).

The rhetorical practice of competitive collusion seems tied to

commercial advertising most vividly in social media and cocreation of advertising. Furthermore, it unpacks the transient

moods, feelings, and attitudes of postmodern citizens whose

fragmented lives are fueled by the dualism of belonging and

egotism. This awareness should sensitize advertisers to ways

of promoting products and services, as well as in competing

with other agencies.

concLuSion

Street art can be considered as an emerging template for commercial advertising and its associated rhetoric. In addition to

the visual and cognitive effect of commercial advertising, street

art also carries messages of enjoyment, ideological critique,

and activist exhortation, while unpacking and demystifying

contemporary urban consumption.

Our multisited ethnographic account describes the various

ways in which street art is a product that embodies its own advertising. We focused on seven rhetorical practices: aestheticization, playfulness and cheerfulness, meaning manipulation, replication, stylistic experimentation, rediscovery, and

competitive collusion. These practices underscore the double

nature of creativity as product and process. We define the product dimension as the “vocabulary” and the process sphere

as the “grammar” (Visconti 2008). Common (street) culture

is the ground that provides a rich vocabulary for advertising:

cheerful images, transfigured pop myths and urban objects, or

logos. Contextually, manipulation, interplay between the place

and the artwork, cartoonification, and other such practices are

pressed into service as their grammar.

Our study asserts that, with thoughtfulness in order to avoid

plagiarism or naive imitation, the rhetorical practices of street

art can be employed to improve the effectiveness, relevance,

and social sensitivity of commercial advertising. They suggest

ways to multiply the sites of advertising, catalyze innovative

and transformative messaging, refresh brands in distinctive

fashion, and engage consumers in a process of cocreation. They

also stimulate a reconnection with the active contemplation

and discussion of images forming the nucleus around which

sociality coheres and occurs. The achievement of any of these

objectives would reinvigorate commercial advertising to a

significant degree.

We have illustrated the potential implications for and contributions to commercial advertising of street art throughout

our account, and we conclude by recognizing the core elements

of street art that suggest synergies with commercial advertising

that might be realized. First, the rhetorical practice of competitive collusion represents a tangle of conflicting and often

unarticulated consumer feelings and beliefs. By combining diverse cultural competencies, novel communication and creative

practices are stimulated, and may prompt the development of

a more viable form of capitalist surrealism.

Second, our informants lament the increasingly melancholic

and paradoxical silence of contemporary urban life. Despite

an overload of communications and networks, urban spaces

are frequently transparent and hold impoverished meaning for

their dwellers. Street art contributes to a transfiguration, aestheticization, and cartoonification of these spaces, and redirects

people’s interest to different forms of consuming experience by

means of a reappropriation of apparently ordinary and takenfor-granted artifacts.

Third, an appreciation of the rhetorical practices of street

art highlights the quest for expressions of communicational

democracy. Commercial advertising creativity can infuse the

drive for familiar communication codes (borrowed from pop

art, streets, consumer communities, etc.), cocreation, and

a peer-to-peer approach (avoidance of top-down visions) in

meaning transfer.

Finally, our data suggest that advertisers must stretch the

boundaries of aesthetics. From more traditional attention devoted to the content of communication, street art has extended

its creative realm to the container through which the message

is conveyed. Relying on aestheticization and playfulness, street

artists are transforming materiel into expressive artifacts. The

synergy between container and contained builds new meanings

for target audiences.

The current interplay of commercial advertising and street

art is fascinating. Street artists’ creativity is steadily stimulated

by advertising provocations and proposals. At the same time,

street art demonstrates an increasing marketability, which even

reinforces its links to the advertising world. The commodification of street art is a vital topic for future investigation.

In an era when people’s symbolic immersion borders on the

overwhelming, when creative industries become so interpenetrating that hybrids proliferate more quickly than scholars’

ability to track them, and when the competitive threats to

advertising of all kinds grow so pervasive, it is useful for

researchers to focus on a discrete arena that hosts a particular

form of creative symbiosis. Our choice of street art as a vehicle for exploring this symbiosis suggests that, no matter the ideological differences in surface structure, the resonant similarities in deep structure between distinctive creative enterprises

encourages a symbiotic relationship to flourish as commented

upon by one artist informant:

In effect, we have something in common with advertising . . . a

deep link. Not only the format: large posters and billboards . . .

also the place: on walls, like advertising. The invasive effect

is the same, the attack is the same. We don’t say, “we’re here,

if you want, read us”; we say, “come over here and read us.”

Our message is that advertising is a form of art, say, poetry,

because it’s a means of linguistic-visual communication,

which through linear, intuitive, emotional paths transmits

messages that go beyond the literal meaning. Like a poem,

when it tells you something, it’s telling you something else

with regard to the literal meaning, the reverse. . . . So does

advertising: it presents ideals, values and, especially of late,

emotions. We do the same thing but . . . the nice thing is that

we can try . . . really try everything. (Matteo, Eveline group

of poetic assault, Milan)

Who is Bozo Texino?

One man's sixteen-year quest to track down the elusive artists of a moniker that's been appearing in railyards across America for 80-odd years is beautifully captured in the 56-minute documentary Who is Bozo Texino? The film debuted in 2005 and since its creator—filmmaker, trainrider and Guggenheim Fellow Bill Daniel—has taken the film on the road to more than 400 venues large and small.

Shot in black-and-white 16mm film with a Bolex camera, Daniel uses the scrawled moniker of Bozo Texino, an expressionless man wearing a large stetson, to explore the themes restlessness and freedom, hardship and entrapment and the many contradictions that exist for those that live on the rails.

BATTLE OF THE ART OUTLAWS • • •

| BATTLE OF THE ART OUTLAWS • • • A front page feature of the Big Issue written by Max Daly, August 25 - 31 1997Fume and Bozo are London's most wanted graffiti artists. The two renegade 20-year olds from West London, who have made their mark on most of the tube trains running through the capital, are the bane of the British Transport Police. The pair are part of a rapidly-growing mob known as 'bombers' - graffiti artists who vandalise trains by scrawling their name in as many places as possible. They have declared war on the more law abiding 'old skool' wall painters, whose work has developed into vast colourful illustrations. The bombers make it their business to ruin the work of all other graffiti artists as quickly as possible, and are equally hostile to what they call 'bumpkins', graffiti artists from outside London. This worsening graffiti war, exclusive to London, surfaced in the form of a punch-up at an annual gathering of graffiti artists - ironically entitled Unity - in Hammersmith earlier this month. The event, held at a disused sunken basketball pitch, was meant to bring together members of the warring underground cliques. But it degenerated into an ugly battle when a London bomber stole a can of paint from a member of the old skool from Brighton. 'It was absolute mayhem. I lost count of the number of fights. There were bottles flying everywhere," says Unity organiser Elk, who reigned supreme on the London Underground in the early Nineties. He is regarded as one of the UK'ss top five old skool writers. 'There were serious fights, people got their backs up pretty badly and the police had to be called. It's a reflection of how rough the graffiti scene is now. These youngsters have no regard for people who were writing when they were still in nappies. They are deliberately upsetting the hierarchy.' If writers are caught tagging (writing their names) in the wrong area, or over existing graffiti they are now likely to get robbed or beaten up. The young breed, whose raids are commonly fuelled by drugs and alcohol, are prepared to go to any extent to get their name known. Fume, who has been working in a gang of 20 since 1992, explains the cause of the fights. 'The only proper writers are on trains, that's where it belongs. Those fighting were mates of ours. The Unity lot just paint walls, we call them 'toys' because they're so lame. They cannot be allowed to dominate us and call themselves writers'. 'If someone has come down from the country you have to nick their tins of paint. That's why the fight at Unity started. It's our fee. You've got to earn the right to be hardcore. If you are not on the line (vandalising tubes), taking risks, then you've got no right to say anything about it. That's the beef: that these people are calling themselves writers and they are not.' According to Fume and Bozo, a bona fide writer must leave the house with no money, and spend the day nicking food, tube tickets and paint to fund their graffiti lifestyle. They say it is like going on a mission. Both claim taggers know more about the workings of the tube system than the drivers and, as a result, have the right to do what they want. 'A real writer is someone who knows how many trains are in each depot and when to pounce; someone who scratches their tag on train windows, paints on them inside and outside,' says Bozo, who adds that getting stoned and arrested is all part of the buzz. 'If you're out with us the whole train has got to be fucked-up. Nothing less will do. It's no use painting the odd wall with pretty colours. You've got to smash every depot. It's a war and no one can control us.' Hundreds of new tags are appearing each year, creating a scrabble for notoriety. If writers are prepared to take the risk to get their name up where others would not dare, reverence is instant. In urban areas, graffiti has become one of the most desirable ways of gaining status. However impossible a tag may seem, somebody will do it. They might get arrested, put in jail or killed, but they'll do it. And there is always someone prepared to take their place. Children as young as 10 are climbing 40 feet up drainpipes and hanging from six inch wide ledges. Many enter areas designed to keep out the IRA. Security guards, railway and Tube depots protected with razor wire, and laser trips which trigger infrared cameras just act as a challenge to most graffiti artists. 'It is one of the most passionate art forms and that's why there is so much friction in London at the moment,' says Elk. 'Writing is about getting your name everywhere. There is a lot of resentment created if someone has got their tag in more places than you. Writers have phenomenal drive and motivation; people will steal paint so they can do it - and for no apparent gain.' Ben, 27, used to tag trains in the early Nineties but avoids writing in London now because of the new breed of taggers. He says it used to be mellow, that writers wouldn't go over other people's work. 'There was a lot of respect, now there is zero respect. London graffiti culture is different from the rest of the England - everybody hates everybody.' Pulse, who has been writing for 15 years, is also disgusted at the wave of in-fighting blighting the London scene, which he describes as being 'the worst in the world at present'. He says youngsters like Fume and Bozo resort to bombing because they can't produce the quality of work achieved by their enemies. 'They have to take the next step and use their imagination,' he says. 'They have no style. The older generation has got to show the youngsters the way forward.' Despite the Unity brawl, old skoolers say the youngsters can still create something positive out of their passion - given time. 'There is not a chance in hell that I can bring these factions all together in peace by waving a magic wand,' says Elk. 'There is too much anger in these people, it is beyond our control now. Hopefully soon they will think what the fuck am I doing. The fact that some of the younger writers were there to see how the older ones work will influence them in the future. They might have been fighting but they were still there. We have planted a little seed which could turn these people into the graphic designers and magazine editors of the future.' |

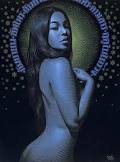

Miles 'MAC' MacGregor

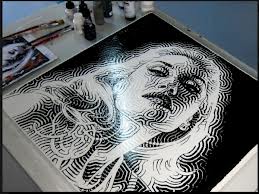

Born in Los Angeles in 1980 to an engineer and an artist, Mac has been creating and studying art independently since childhood. He was inspired at a young age by classic European painters such as Caravaggio, and Vermeer and Art Nouveau symbolists such as Klimt and Mucha. This was mixed with the more contemporary influences of graffiti and photorealism, as well as as the Chicano & Mexican culture he grew up around.

He began painting with acrylics and painting graffiti in the mid ’90s, when his primary focus became the life-like rendering of human faces and figures. He has since worked consistently toward developing his unique rendering style, which utilizes repeating contour lines reminiscent of ripples. Turing patterns and indigenous North American art. In 1999 he began to paint portraits of his friends and anonymous Mexican Laborers in public spaces throughout the American southwest, both legally and illegally. He also started painting large technicolor aerosol interpretations of classic paintings by old European masters. This led to being commissioned in 2003 by the Groeninge Museum in Brugge, Belgium to paint his interpretations of classic Flemish Primitive paintings in the museum’s collection. He has since been commissioned to paint murals across the US, as well as in Mexico, Denmark, Sweden, Canada, South Korea, Belgium, Italy, The Netherlands, Puerto Rico, Spain, France, Singapore, Germany, Ireland, the UK, Vietnam and Cuba.

Some of his murals have become local landmarks, especially his collaborations with Retna, which combine Mac’s representational figures with Retna’s typography and designs. The majority of their collaborations have been painted in LA, though a few notable murals were painted in Miami’s Wynwood Arts district for Primary Flight/Art Basel from 2007, 2008 & 2009, including one painted on the Margulies Collection building. Mac and Retna had an important exhibition together, “Vagos y Reinas: at the Robert Berman Gallery at the Bergamot Station in Santa Monica in 2009. Alianza, a book documenting their individual and collaborative works was published by Upper Playground/Gingko Press that same year.

Mac’s art was featured on the cover of Juxtapoz magazine in 2009 and again in 2012, as well as the cover of LA Weekly for a feature on the Seventh Letter collective. In the last few years he has had successful solo exhibitions at Fifty24SF Gallery in San Francisco (2009), and Joshua Liner Gallery in NYC (2010). In 2010 he also painted a large mural on the museum of contemporary art (MARCO) in Monterrey, Mexico as part of the Seres Queridos project. In 2012 he painted a large mural in Havana, Cuba for the 11th Havana Biennial sponsored by the Cisneros-Fontanals Art Foundation.

Mac continues to balance his love of painting large-scale public artworks around the world with his meticulous and time-consuming creation of indoor works. He aims to uplift and inspire through his careful, perfectionist renderings of both the sublime and the humble.

He lives and works in Los Angeles.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)